By Randy Horick, BA'82

Fifty years ago Vanderbilt University was finally, irrevocably, on its way to launching a graduate business school. After a decade of informal discussions and formal presentations,

the university made its commitment and was actively soliciting major donors among both individuals and foundations. Vanderbilt had even secured a building for the new school:

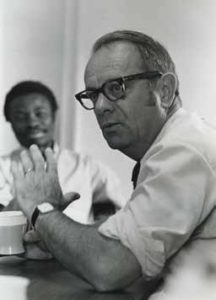

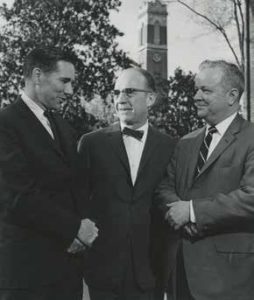

the former Cosmopolitan Funeral Home on West End Avenue, which was donated by trustee Pat Wilson, BA’41. The main task that remained by the spring of 1968 was to find a dean who could develop a new curriculum, recruit faculty and students, and launch the school. To manage such a monumental undertaking, and to create what Vanderbilt’s trustees hoped would be a school “of the first rank,” would require an exceptional talent. The man ultimately selected for the task did build a program from scratch that was unlike any other U.S. business school—before or since. In one sense, at least, Vanderbilt leaders had a head start as they began their search. During the years of discussion, Vanderbilt’s leaders knew they wanted to create a unique school led by an innovative dean. They hoped to integrate the perceived strengths of the case-study and quantitative models while avoiding their perceived weaknesses. Influenced by widely read assessments of the state of business education, they also favored a “generalist” approach grounded in academic rigor over what some called vocational training. With that in mind, Provost Nicholas Hobbs sent letters to 123 graduate schools of business soliciting suggestions for potential deanship candidates. As he reported to the board in May 1968, he began with 250 names, winnowing that list to around 30. Of these, a third removed themselves from consideration. Another 12 to 15 failed to meet Hobbs’ expectations. But a professor at Carnegie-Mellon, “one of the top 10 scholars in the field of business management, has shown a lively interest in the job,” Hobbs said, according to minutes of the meeting with trustees. “He is a man with an excellent academic background and extensive

business experience.” Igor Ansoff seemed ideally suited for Vanderbilt’s ambitions. His background melded teaching and research with senior management experience at Lockheed, where he’d led strategic planning, and the RAND Corp. Fluent in Russian and German, he had consulted with top organizations all over the world. His books and articles on strategy were influential. At a meeting of the Vanderbilt Board of Trust’s executive committee in June 1968, Chancellor Alexander Heard reported that the job of dean had been offered to Ansoff, whom he described as “by all odds the best man available in the country.” He noted that several foundations (all potential sources of financial support) had endorsed Ansoff “with enthusiasm.” Heard wanted freedom for Ansoff to maneuver—and experiment. “It is necessary to realize,” he told the board, “that the dean will have certain attitudes and a vision of what he wants the new school to become, and to a certain measure the new school will be built in his own image.” They were soon to find out how right Heard was—and how far from traditional business education Ansoff wanted to take Vanderbilt.

“Poverty, racism, the deterioration of the inner city, air and water pollution, public education, recreation, housing, transportation, nutrition, health care, political effectiveness, the adequacy of the judicial system, population control—these must all be the informed concerns of the modern manager. ”

—Igor Ansoff

MANAGEMENT REIMAGINED

“The proposition that the business of business is solely business,” Ansoff wrote, “has become untenable.” Instead, he argued, businesses must understand themselves as organizations whose well-being is inseparable from the well-being of society. As Ansoff saw it, according to a 1969 Vanderbilt Alumnus article, while businesses had fostered an era of unprecedented material prosperity, these gains had also begotten a number of ills—from “lopsided” distribution of wealth to concentration of power among huge corporations—and business should help remediate them. “Poverty, racism, the deterioration of the inner city, air and water pollution, public education, recreation, housing, transportation, nutrition, health care, political effectiveness, the adequacy of the judicial system, population control—these must all be the informed concerns of the modern manager, whatever his affiliation,” read the strategic plan that Ansoff and Hobbs developed for the school.

Owen’s first home was Henry Clay Alexander Hall—the former Cosmopolitan Funeral Home on West End Avenue.

It was therefore important, Ansoff insisted, that Vanderbilt prepare students to become managers of “purposive organizations,” starting with businesses but encompassing all sectors. With a mathematician’s faith in solutions—Ansoff held a Ph.D. in applied math along with master’s degrees in engineering, math and physics—he believed that it was now possible to apply learning from the business world to all organizations and to elevate management from an art to a science. Producing “effective managers of change” in a rapidly changing society, he argued forcefully, would make Vanderbilt one of the first schools in the country with “such a single-minded focus.”

Earlier in the meeting when they decided to hire Ansoff—a month after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr.—the board had spent much of its time discussing the university’s urgent need to recruit more African American students and make them feel welcome. They hardly needed the reminder Heard offered them that the world they’d all grown up in was rapidly changing. Ansoff’s timing seemed perfect.

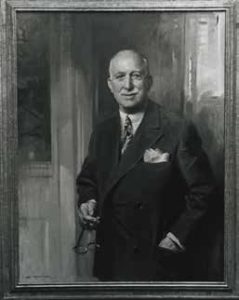

Ansoff envisioned an unconventional graduate business school experience, elements of which are still alive today at Owen.

The school’s name, Ansoff believed, should reflect its distinctive focus on managing change. At the first meeting of the trustees’ executive committee after his hiring, he proposed dropping the word “business” in favor of the Vanderbilt Graduate School of Management. It would become the first test of Ansoff’s experiment. With Heard and Hobbs behind the idea, the committee approved the name change. But when the proposal reached the full board, not everyone was enthusiastic. Frank Houston, BA 1904, honorary chairman of Chemical Bank, worried that such a name might confuse the business community about the school’s program. In one of three letters he wrote to Heard, Houston said that several trustees shared his concerns. He proposed a compromise: the Vanderbilt School of Business Management. Upon further deliberation, however, the executive committee reaffirmed its earlier recommendation. Their case was bolstered by a major development in the winter of 1968–69: Ansoff had rekindled a sputtering courtship with the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which liked his ideas. The foundation committed $500,000—a sorely needed financial boost. It would be awkward if officials at Vanderbilt returned to their angel donor with news that the new program might be more traditional than what they’d enthusiastically supported. Instead, Ansoff recommended (perhaps at Heard’s suggestion) that the school endow a Frank Houston Professorship of Banking and Finance, which it did, along with commissioning a portrait of Houston that hangs in Management Hall to this day. After that, the records provide no further evidence of disagreement about the name. It would be called the Graduate School of Management—GSM for short.

MASTER OF MANAGEMENT

The portrait of Frank Houston, which helped diffuse some disagreement, still hangs in Management Hall.

What Ansoff devised, working closely with the provost during an intense year of planning, turned his vision into a radically distinctive structure. Vanderbilt would offer a master of management degree, not an MBA. As a compromise to those who feared the new school was venturing too far afield, it also offered a master of business management degree.

In his proposal for the M.Mgt., Ansoff wrote that the goal was to “produce professional managers who are attuned to the needs of society.” While business remained “a major focus,” students would examine many types of institutions, with an emphasis on general knowledge and skills that could be applied broadly.

The curriculum would strongly emphasize organizational behavior. The core M.Mgt. classes included Organization and the Environment, Organizational Change, Individual Behavior in Organizations, Theories of Organizations, Comparative Organizations and Organizational Strategy. Students also would complete courses in Learning to Learn, Logic and Methods of Inquiry and Computers, and often read from work in psychology, philosophy and literature.

GSM would break other traditional molds, too. “God,” as Ansoff liked to say, “did not invent the 15-week semester.” Instead, learning modules would be of indefinite length—some as short as two weeks. Experiential and self-directed learning were elevated; in fact, students could shape much of their second year with independent study involving projects in the local community. Meanwhile, the school would innovate with “technical aids”—including video, computer simulation exercises and “self-testing devices”—designed to make learning not only more effective but less expensive. Eventually, curriculum modules were to be largely automated to help students progress at their own rate.

Everyone understood that the program was experimental. They believed the risks were worth taking. If the GSM achieved only 25 percent of its goals, as Ansoff was quoted in the Nashville Banner from a speech to the Nashville Rotary Club in 1970, it would nevertheless make a “significant impact.” If it achieved half its goals, it would become a “renowned school.” And if they were completely successful, he joked, “we will become impossible and won’t talk to anyone.” “We were convinced that the world did not need another run-of-the-mill graduate school of business,” recalled one original faculty member. “If we couldn’t do something innovative, we might as well fold up our tents and go home.”

Unfortunately, a plan that called for experimentation did little to build confidence among the business community—and some employers were concerned that so many of

the students seemed interested in fields other than business. One executive is said to have asked Ansoff, “What kind of monsters are you creating?” The business community’s concerns were reflected in lackluster financial support. They didn’t know quite what to make of the quirky little school and its innovative approaches. Planning for so many graduates to enter the nonprofit sector did not serve a community seeking graduates ready to fill more traditional business roles. The challenge was complicated by an understandable position taken by Heard and the board—that Ansoff should focus on launching and operating the school rather than fundraising.

Hobbs (center) talks with Chancellor Alexander Heard (left) and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Rob Roy Purdy.

As Professor Robert Ullrich remembered it, the Board of Trust “became disenchanted” with both the school’s model and progress. The faculty, recruited with clear intent to reflect diverse and even conflicting points of view, was divided. There was much dissension, Ullrich recalled, “between those who wanted to innovate and those who wanted to pull back.”

The financial struggles became a crisis in 1973, when the GSM had to borrow from general university funds. By that time Ansoff had stepped aside as dean, though he remained on the faculty. Within a year he left Vanderbilt for teaching appointments in Europe. Under new leadership, the school would adopt a much more traditional approach.

Google Igor Ansoff’s name, and you’ll quickly notice the accolades. The Economist described him in 2008 as “the father of modern strategic thinking” and “one of the world’s most influential management thinkers, past and present.” His book Corporate Strategy was ultimately translated into seven languages. Prestigious awards for strategic planning and management bear his name in Japan and the Netherlands. There’s also an Igor Ansoff Award at Vanderbilt, recognizing original and creative contributions to today’s Owen School.

But given his outsized reputation in the wider world, Ansoff remains relatively unheralded at the school he helped launch. One explanation may be that Ansoff’s legacy is widely viewed, as Dean M. Eric Johnson summarizes it, as “an interesting, quirky experiment that failed.”

And yet, Johnson adds, “When you talk to students from that time, I’ve never heard a negative thing about him. I don’t get a sense they felt let down.” In fact, Ed Alston, the first student to receive a degree from the new school in 1971, credits Ansoff when asked about the most important lesson he took from his Vanderbilt experience. “His expertise was in strategic planning, and strategic planning has been a big contribution to my success”—both in corporate America, he says, and in his personal life. “That has carried me for a long time.”

Notwithstanding that the school underwent a reboot, Ansoff’s legacy also endured in ways that Owen celebrates today. You can connect some of the school’s distinguishing hallmarks—the close community where students and professors are on a first-name basis; the emphases on change management and entrepreneurship; the focus on experiential learning; students’ freedom to shape their learning experience; and, of course, the Graduate School of Management name—to Ansoff’s original vision. “The teams and collaborative work were baked in from the beginning,” Johnson says. “So was the school’s commitment to diversity—and diversity of thought. That was pretty revolutionary at the time.”

At students’ invitation, Ansoff offered his own assessment upon his departure. He acknowledged that “a number of our expectations did not materialize.” But he also said that, somewhat to his surprise, much of what he had envisioned was in place or in progress. He did not have to state what his audience already knew: that Vanderbilt now had a school of management that was internationally known. “Maybe we were too ambitious,” Ullrich reflected in 1989. “We really thought we could reform higher education in a couple of years. But we must have done something right, because many of those early graduates have done great things.”

Randy Horick, BA’82, owns Writers Bloc Inc. and is a Nashville freelance writer and editor. With an undergraduate degree in history and journalism from Baylor University, the former advertising copywriter earned his master’s in history at Vanderbilt.