By Lacie C. Blankenship

For decades, working women’s negotiation skills have frequently been blamed for the gender pay gap. New research by Vanderbilt Professor Jessica A. Kennedy finds that the gendered tendency to negotiate has now reversed, and the widespread narrative that women don’t ask for fair pay is outdated. While other measures are necessary to close the gender pay gap completely, the study also discusses how people who believe and adhere to the notion that “women don’t ask” hinder progress.

“Our research shows that women are willing to do their part to close the gender pay gap. Unfortunately, negotiating well isn’t enough to close the gender pay gap. It’s not the source of the problem,” says Kennedy.

What is the gender pay gap?

Working men make more than working women at every wage level. At higher income levels, the gender pay gap is the widest. The statistics on the gender pay gap refer to incomes in percentages, as in for every dollar a man makes, a woman makes a percentage of that dollar.

Working men make more than working women at every wage level. At higher income levels, the gender pay gap is the widest. The statistics on the gender pay gap refer to incomes in percentages, as in for every dollar a man makes, a woman makes a percentage of that dollar.

Recently, new census data revealed that the gender pay gap has widened for the first time in two decades, with full-time, year-round working women’s median earnings of 82.7% compared to their male counterparts. This percentage is down from 2022 when women earned 84% of what men did. Studies have also shown that after completing MBA degrees, women typically make 88% of what men earn, and the gap widens to 63% ten years later. It is critical to note that women of color experience more significant pay discrepancies than other women.

“Sometimes I have concerns that comparing men and women fuels an unproductive gender war instead of illuminating the real issue, but the point is that employers should be paying in justifiable, transparent ways with equal pay for equal responsibilities,” says Kennedy. “A pay gap by itself doesn’t necessarily indicate unfairness, but too often, it causes people to invent false narratives about people who command fewer resources, and that’s a real problem. We can’t deal with a problem we don’t see accurately.”

To challenge a false wage gap narrative, Kennedy co-authored a new publication titled “Now, Women Do Ask: A Call to Update Beliefs about the Gender Pay Gap.”

The findings from this set of studies debunk the widespread belief that gender differences in the tendency to negotiate are a critical explanation for the pay gap. Kennedy conducted this research with Professor Laura Kray and Post-Doctoral Scholar Margaret Lee at UC Berkeley. Read more about the studies below.

Now, Women Do Ask.

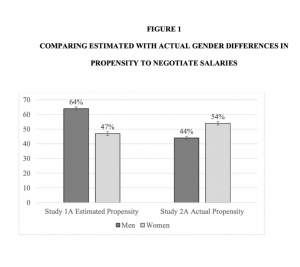

With a nationally representative sample, the authors first established that people believe men negotiate their salaries more often than women do. Generally, people estimated that 64% of men and 47% of women negotiated job offers. Next, the authors compared these percentages to the real figures using three different datasets.

“It was interesting and refreshing to see the nuance in people’s beliefs about gender. People believed women were negotiating less often than men, but they also believed women faced discrimination too,” says Kennedy. “People thought women were less likely to get what they asked for, recognizing asking as an imperfect solution.”

How was this uncovered?

Figure 1

Two studies utilized data from graduating MBA students and alumni from a top U.S. business school. In both studies, women reported negotiating their job offers more (not less) often than men. The authors then re-analyzed data from prior studies with a broader sample, corroborating the results with a greater scope. Finally, they examined the downstream consequences of believing women negotiate less often than men.

In one study, 990 participants who graduated from business school between 2015 and 2019 were asked a series of questions about their job search, the essential one being, “Did you negotiate your job offer?” Fifty-four percent of women reported negotiating offers compared to 44% of men, contradicting the idea that women don’t ask.

In a second study, nearly 2,000 business school alumni respondents provided details about their compensation and negotiation behaviors, including successful and unsuccessful attempts. In this study, the gender pay gap was 78%. The study revealed that 64% of women and 59% of men reported trying to negotiate for promotions or better compensation. Again, this contradicted the idea that women don’t ask. In addition, the study found a slight difference whereby 4% of men and 7% of women reported unsuccessful attempts to negotiate raises. Generally, negotiating worked; more attempts to ask were associated with better compensation.

To examine the generality of these findings, the authors then re-analyzed data collected from various samples between 1982 and 2015. In this study, which involved 5,108 people, the researchers found no evidence of a gender difference in negotiating propensity. Men and women were initiating salary negotiations at similar rates. Examining the trend over time, the gender difference in negotiating rates declined. While it may have once been true that women negotiated their salaries less often than men, the trend no longer holds and may have reversed, at least in some populations.

Why does this matter? Outdated Beliefs Have Consequences.

Professor Jessica A. Kennedy

Two later studies explored the consequences of negotiation-based explanations for the gender pay gap. Study Three focused on support for legislation designed to support pay equity. First, Kennedy and her co-authors asked participants what percentage (from 0% to 100%) of the gender pay gap they believed was attributable to three different types of explanations. One type of explanation pointed to women’s and men’s negotiation abilities. Another type pointed to women’s choices, such as number of hours worked; a third type pointed to issues of fairness. When people attributed the gender pay gap to women’s negotiation abilities, they were less inclined to support legislation that renders it illegal to consider a candidate’s salary history when setting the current salary for a position. They were also more likely to endorse statements like, “Society is set up so that men and women usually get what they deserve.” Results suggest that people who believe women negotiate less are less inclined to support policies to reduce the gender pay gap.

In Study Four, the researchers explored the consequences of negotiation-based explanations for broader gender stereotypes. Participants were exposed to a passage from a book that conveyed the “women don’t ask” message or to a passage about the importance of negotiation. Exposure to the “women don’t ask” message promoted endorsement of gender stereotypes along other dimensions, such as believing women are more nurturing and men are competitive. In addition, it increased belief in personal choices as justifications for the gender pay gap.

“Men and women have actually become more similar over time, as their roles have converged, so viewing them as very different is a problem,” says Kennedy.

What next?

Since the pay gap still exists and has recently widened, despite women’s strong negotiating skills, it’s time to stop blaming working women for not doing their part. The researchers behind the study call for an update on beliefs about gender and the tendencies to negotiate for higher pay.

“It’s time for employers to take a clear look at how they pay people. Let’s be sure we fix the system and get over the idea of fixing the women. The women don’t need fixing,” says Kennedy.

Now, Women Do Ask: A Call to Update Beliefs about the Gender Pay Gap was published online by the Academy of Management Discoveries in August 2023.