By Lacie C. Blankenship

Joshua T. White, Assistant Professor of Finance and Brownlee O. Currey Jr. Dean’s Faculty Fellow at Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management, was invited to testify before Congress in Washington D.C., in the Spring of 2024. White testified before the House Financial Services Committee in the hearing entitled “Beyond Scope: How the SEC’s Climate Rule Threatens American Markets.”

White opened his prepared testimony by thanking Chairman McHenry, Ranking Member Walters, Vice Chair Hill, and the members of the Committee on Financial Services for inviting him to participate in the discussion and included a brief introduction where he nodded to his experience serving as a financial economist and expert consultant in the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). He also highlighted his academic contributions, which include evaluating the effects of SEC rule changes published in esteemed law reviews and prominent finance and accounting journals. Furthermore, he noted that the U.S. Court of Appeals referenced his recent critique of the SEC’s economic analysis on a stock buyback disclosure rule, which contributed to the vacating of the rule.

“It is my opinion that the adopted rule on climate-related disclosure will ultimately harm capital formation, deter companies from going public, reduce employment, and limit investment opportunities for ordinary investors,” said White.

The SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rule

The SEC recently implemented rule amendments, known as the Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors (the final rule(s)), requiring the inclusion of specific climate-related information in the registrations and annual reports of public companies and public offerings.

This means that public companies must share intimate details of their climate-related efforts. Specifically, this rule requires companies to share information like how they deal with climate-related risks, who oversees those risks, and how they track their climate-related goals and progress. Other requirements include that larger-scale companies must report how much greenhouse gasses they produce with the confirmation of a third party and that companies with goals related to climate change must publicly disclose the financial implications of those goals.

In his testimony, White thoroughly explained the required disclosures from the new mandates. He also noted that the new climate disclosure rule “has double-digit instances where the SEC notes that ‘[they] decline’ to follow or recognize suggestions recommended by commenters.”

Professor White’s Congressional Testimony

After his introduction, White jumped into his inspection of the economic analysis behind the mandate, including its alleged costs and benefits. “I will highlight specific shortcomings in the SEC’s economic analysis and conclude that the final rule lacks a fully justified cost-benefit analysis,” he said. Read below an overview of the key points White shared in his testimony.

Estimated Costs of the SEC Climate Disclosure Rule

White noted that several new disclosure requirements will result in higher (direct and indirect) costs.

“The costs of the climate disclosure rules will differ widely based on the size, industry, complexity, and other attributes of SEC registrants,” said White. As part of his testimony, he then provided a table replicating the SEC’s estimated compliance costs.

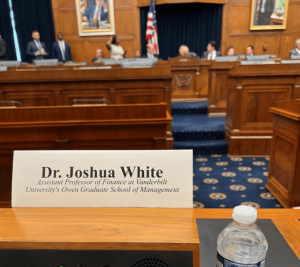

White provided a photo from his perspective when he testified before Congress in the Summer of 2023

White testified that the implementation of the final rule is alleged to increase the annual “burden” for reporting to the SEC as a public company by 18% while also noting that the SEC “likely significantly underestimates the compliance costs for the new climate-related disclosure rules,” citing a 2009 SEC study showing the compliance costs for Section 404(a) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 were 367% higher than the SEC’s estimate in the final rule.

White went on to dissect the indirect costs of the final rules, including an increased litigation risk for companies. “Registrants could be subject to allegations that their climate disclosures contain materially misleading statements or omissions, in violation of securities laws,” he said. Another indirect cost is the concern that disclosing intimate, proprietary information to competitors would disadvantage public companies and incentivize firms to go or remain private. Lastly, White discussed the potential indirect cost of “investors’ tendency to overly fixate on salient information in SEC filings.” He demonstrated the relevance of this notion by pointing to his research findings that when companies try to simplify their reports on complex issues, like Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG), investors put too much emphasis on the simplified numbers; however, distilled metrics cannot capture the holistic picture.

Purported Benefits of the SEC Climate Disclosure Rule

White dedicated part of his testimony to outlining the alleged benefits of the SEC Climate Disclosure Rule with a rebuttal for each point.

“The SEC claims that the primary benefit of the rule is to provide comparable, consistent, and reliable disclosures of climate-related information,” he said. “However, the economic analysis fails to demonstrate how the proposal will generate comparable, consistent, and reliable disclosures.”

The concepts White discussed include a theme of ambiguity attached to the SEC Climate Disclosure Rule. For example, he noted that the SEC’s economic analysis claims that investors will be better equipped to make decisions on climate-related topics; however, there is no clarity on the specific differences the rule implements.

White also touched on the specious notion that the SEC’s economic analysis suggests that the already publicly available climate-related information affects stock prices and that requiring additional granular disclosures will not likely be any more beneficial.

“The SEC cannot assert that costs will decrease for registrants already sharing this [climate-related] information—which is already reflected in their stock prices—without conceding that the benefits will also diminish,” said White. Such selective discussions in the SEC’s economic analysis have parallels with the claims of “cherry picking” climate information that the SEC criticizes in its final rule.

Additionally, the addendum implies that providing more intimate climate-related information could be beneficial to investors who prioritize climate-related risks; White’s counterpoint was that this “benefit” towards one group of investors raises questions of why one group should get preference or benefits over other groups of investors who focus on other risks like supply chain issues or currency fluctuations.

Other Shortcomings in the SEC’s Economic Analysis

In the third section of his testimony, White outlined additional problem areas of the SEC’s economic analysis that “warranted attention prior to the promulgation of the amendments.” These shortcomings included the lack of argument for deviating from the existing framework, the failure to acknowledge the merits of a principles-centric approach (which guards against revealing sensitive information unless materially significant), and minimal analysis of the impact on capital formation.

In a Wrap: Underestimated Costs & Overclaimed Benefits

In concluding remarks, White reminded the Committee of the overarching concepts he carefully detailed in his testimony.

The SEC Climate Disclosure Rule “likely has underestimated costs and overclaimed benefits,” he said. “These amendments introduce highly detailed climate-related disclosure requirements, which I show are not supported by a thorough and balanced cost-benefit analysis. The final rule mandates extensive mandatory disclosures that will impose substantial direct and indirect costs on registrants.”

Note: Vanderbilt University faculty, staff, and students who speak in Congressional hearings represent themselves as individuals and do not speak on the institution’s behalf unless specified otherwise.