By Cal Turner Jr., BA'62

I was 15 years old when my dad, Cal Turner Sr., took the step that changed everything. It involved the kind of creative leap that comes along all too rarely, and it ultimately left a huge mark on American business.

J.L. Turner and Son, as it was called then (James Luther Turner was my grandfather), had 36 retail stores, generally partnerships with local merchants, in small Kentucky and Tennessee towns. The business, headquartered in Scottsville, Kentucky, was grossing about $2 million annually, and my dad was always looking for ways to grow. He was a keen observer of both his customers and the competition, and he became intrigued by the “Dollar Days” sales put on by the big department stores in Nashville and Louisville. Once a month, they would take out huge full-color newspaper ads and sell merchandise with $1 as the single price point. My dad knew what those ads cost, and he understood that if they were spending that kind of money, they were selling a lot of goods. Customers obviously loved that $1 price point. Somehow, it made real value seem even more obvious.

“Why couldn’t we simplify all of our operations,” he thought, “by opening a store with only one price—a dollar?” Every day would be Dollar Day. In that flash of insight, he saw any number of benefits. Customers could keep track of what they were spending more easily, and checkout would be simplified.

My dad was convinced he had something. He walked into work the next day and asked his management team to join him in his office. He told them he wanted to sell everything in every store for $1. In some cases it would be multiples, like three plates or two pairs of socks for $1, but nothing would cost more. “What do you think?” he said.

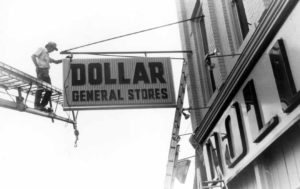

“Cal,” they told him, “it’ll never work. You can’t buy enough merchandise to sell that cheap!” They were especially concerned about apparel, since so much of it sold for more than $1. But Cal Turner Sr., who had been a student in Vanderbilt’s School of Engineering in the 1930s, was the classic entrepreneur—he followed his gut, and his gut told him this would work. He trusted his knowledge of customers more than he trusted the opinions of even those closest to him. He decided to do it. He would start with a store that had failed. It was in Springfield, Kentucky, and it had operated at a loss as a junior department store. It would provide a great test of whether this new concept would work. That left choosing a name. The word “Dollar” was a must—that was the whole point. With a nod to the term “general store,” he added the word “General.” He was an opportunity buyer. He looked for bargains, and the word “General” would let customers know they might find just about anything inside. He often said, “Back in the country, the general store was where everything and anything was sold.” The Dollar General sign, he decided, would be black and yellow, a combination he knew really stood out. “I wanted the colors to leap right off the store signs,” he said.

The opening was set for Wednesday, June 1, 1955. Turner’s Department Store on Main Street in Springfield would become the first Dollar General store. The layout was clean and simple, with big bold red $1 signs seemingly everywhere. Its slogan was “Every Day Is Dollar Day.”

The “high-tech” activity of opening a Dollar General store in the early days was a bit different than today.

On the big day, people crowded around the front of the building by the hundreds. The manager knew he wouldn’t be able to let them all in at once, so when he opened, he let customers in until the place was good and crowded and then shut the doors behind them. As they came out, he let new people in. He and my father had a hit on their hands, and my dad had a concept he could take to other stores in the chain—where the scene of huge crowds at grand openings would be repeated over and over.

The second store was in Memphis. Dad bought the Goodwin Crockery Co., a wholesaler with an office and a big warehouse on Union Street. It wasn’t exactly a prime retail market; there were used car lots here and there and not much else. Dad loaded the building with merchandise and opened for business. Selling nothing for more than $1, that store had sales of $1.1 million in the first 10 months—“a million, one hundred and thirteen thousand dollars,” my dad said to me. “Isn’t that amazing?” Dad knew he had something.

He opened and converted other stores, eager to reproduce that early success and always looking for the next opportunity. My dad knew he was changing the customers’ entire way of thinking. This was a different way to present value, avoiding common price points like 49 cents, which would now be two for $1. In his stores, they wouldn’t be looking at a host of individual prices anymore. They’d be thinking, “Look what I can get for a dollar. I can get 10 of these forks or four of these saucers, and since I can mix and match, I can get five forks and two saucers for a dollar.”

He was changing the approach of his buyers as well. He had always worked with a few people who could deal with vendors and haggle over the prices for everything but the clothing he so loved dealing with, but my dad didn’t believe in having a lot of buyers. For a long time he had been the buyer, and gradually he’d been training people to do what he did. Still, it was a long, slow process for him to get to the point where he’d trust them to implement the decision-making he’d honed through the years.

Traditionally, it had been, “I’ll negotiate the best price I can, then add my 30 percent markup, and that will be the retail price.” Now they’d have to think in terms of one price point—$1—and then common-sense multiples like two for $5, something that became clear after he’d priced shoes at $1 apiece to conform to his slogan, “Nothing over a dollar.” Some people would buy just one! He wound up with mismatched shoes, so he went to $2 per pair of shoes, and other multiples of $1 weren’t far behind. The important thing was that each bill in a customer’s pocket represented a unique and easily understood price point. He or she would know what each would buy.

Each price point would have to mark a clear step up in value. As a buyer bought for the upcoming Christmas season, he’d be thinking, “What is the best stocking stuffer we can offer a customer for a dollar? What kind of gift or toy can we price at $5?” Then, “What is going to be the one big toy for that child that we can offer at $10?” You’d have crisp, differentiated levels of value in your store, and your customer could understand the system and keep up with what she was spending. My dad knew it would require real discipline.

“With the dollar strategy, the discipline is forced on you,” he said. “With virtually every item less than $10 and with the pricing at one-dollar breaks, there is not much room to stretch. Price-point retailing takes nerve, and we’ve had the nerve. We have to be better merchants to operate in this niche. We have to ‘cream the lines’ we carry to have the greatest possible offering in a small store. We have to make every item count. We have to recognize that if we make a mistake, we’ve got to get it out of there quickly. I’m not one for false pride.” Dad knew there were times they’d have to sell below cost to give the best deals possible to the customers while sticking with that $1 price. If he was buying, for example, cold-pack canners—big covered pots used in home canning—he might pay $12.75 a dozen. He knew they’d make great $1 items that would help bring in customers, so that’s where he’d price them.

On the other hand, he might be buying cheap ceramics from Japan at $5 a dozen. He’d price those at $1, too. He wanted the store employees thinking they were making a profit on everything they sold, to keep them smiling through both sales, and he’d handle the markup at the wholesale level. He’d bill both items to the stores at $10 a dozen, and they’d sell them for $1 apiece, or $12 a dozen, a markup of $2 per dozen.

Meanwhile, the warehouse was getting $20 from the store for items for which it paid a total of $17.75. The ceramics covered the loss they would have shown on the canners. That way, they wouldn’t show a loss of $2.75 on every dozen cold-pack canners. For good measure, it would mystify his competitors, who knew Dad was selling those canners for less than they were buying them wholesale and wondered how he could possibly be getting such a good price. Sometimes he knew he’d have to go to the vendor and say, “I can’t pay you that much. I’ve got to sell this at a dollar. Can you work with me?” He would actually become an agent for the customer. It would take discipline and stubbornness, qualities Cal Sr. had in abundance.

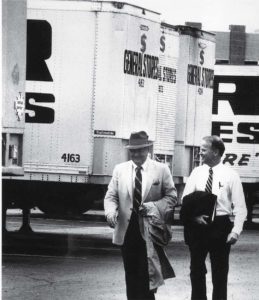

Cal Turner Jr., left, and Cal Turner Sr. chat outside a store in Scottsville, Kentucky, where their company began. Today, Dollar General is headquartered just outside Nashville, with stores

in 44 states.

One early episode epitomized the popularity of the store and the effectiveness of good pricing. My dad’s friend Guy Comer, who owned Washington Manufacturing Co., was drowning in pink corduroy material at the end of a short-lived pink-and-black craze. Struggling to sell anything and everything he could for $1, my dad said, “Why don’t you cut that up and make men’s pants that I can sell for a dollar?” Mr. Comer wasn’t able to do it quite that cheaply, but he came close enough that Daddy bought a lot of them at far less than he’d have to pay for other pants of that quality. There was nothing else Mr. Comer could do with the material, so he went along. My dad would be selling them at a loss, but they’d bring people in the store. He sold them at $1 a pair—50 cents a leg—and his customers were practical enough that, regardless of the gaudy pink color, they recognized value and bought them. And although it was summer, they wore them. Through the years people have told stories about visitors to Springfield being confronted that summer with downtown streets that had a decidedly pink hue!

In 1955 my dad and grandfather incorporated the business, which included 36 stores in partnership with local merchants. These were self-service stores, as opposed to the old general store, where the proprietor would gather the things you wanted, or the department store, where a clerk helped you with your purchase. Self-service opened the whole store to the customer. There was a price on every item, and you helped yourself. The cash register was near the front door. The stores carried apparel, shoes, domestics (things like towels and pillowcases), and household items of every sort.

The number of stores stood at 29 in 1957, as a few of the less successful ones had closed and partners had bought Dad out in others, but sales had more than doubled to $5 million. Small-town merchants began coming to Scottsville, seeking to become part of Dollar General. My dad never sought out franchisees, but he welcomed those who came. He also hand-picked some people to work with. His approach would work even with managers who hadn’t worked in retail before. When one told him he didn’t know anything about running a store, my dad said, “If you knew anything about running a store, I wouldn’t want you. I want to train you myself.” That training, repeated over and over, would help take his already successful idea to undreamed-of heights.

Excerpted from My Father’s Business: The Small-Town Values That Built Dollar General into a Billion-Dollar Company by Cal Turner Jr. with Rob Simbeck (© 2018). Used with permission from Center Street, a division of Hachette Book Group Inc.

ABOUT DOLLAR GENERAL

The first Dollar General store opened in Springfield, Kentucky, on June 1, 1955, and the concept was simple: No item in the store would cost more than a dollar. The idea became a huge success, and other stores owned by J.L. Turner and his son Cal Turner Sr. were quickly converted. By 1957 annual sales of Dollar General’s 29 stores were $5 million.

The company went public in 1968 as Dollar General Corp., posting annual sales of more than $40 million and net income in excess of $1.5 million. In 1977, Cal Turner Jr., BA’62, who joined the company in 1965 as the third-generation Turner, succeeded his father as president of Dollar General. Cal Turner Jr. led the company until his retirement in 2002. Under his leadership the company grew to more than 6,000 stores and $6 billion in sales. Today the company is one of the nation’s leading discount retailers, with more than 15,000 stores in 44 states.